TEDD GRIEPENTROG

Saxophone Journal

Cover Story / Interview

by Dr. Jerry Rife

Saxophone Journal cover

Jan/Feb 1995

U.S. Army Field Band

on the U.S. Capitol steps

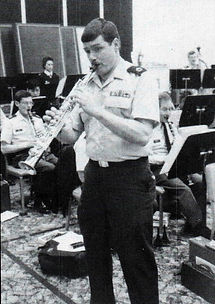

Tedd Griepentrog rehearsing

Jim Richens' Capriccio

To hear a recording of Jim Richens' Capriccio, A Tribute to Rudy Wiedoeft, and other performances by Tedd Griepentrog, click here.

Field Band Saxophone Quartet

Sheila Connor, Tedd Griepentrog, Jim Burge, and Anjan Shah

Field Band saxophone section

(L to R) Sheila Connor, Anjan Shah,

Tedd Griepentrog, and Jim Burge

Few would argue that the world of a professional saxophonist is highly competitive or that making a living playing “classical” saxophone is one of the rarest jobs on earth; yet, at the age of thirty-six, Tedd Griepentrog has already established himself as a successful performer and truly has made the saxophone his career.

Foremost in his mind is his belief that a saxophonist should be a great musician who just happens to play the saxophone. This dedication to music and his love the of the saxophone are supported by a broad musical background, an inexhaustible commitment to the highest musical standards, and a remarkable ability to communicate verbally and musically. Our interview at Fort Meade, Maryland, convinced me that the saxophone world has in Tedd Griepentrog its most articulate and passionate spokesman. I also attended a rehearsal of the U.S. Army Field Band in Devers Hall on the base and heard Tedd play Capriccio for Soprano Saxophone and Wind Ensemble by James Richens. Tedd played very demanding passages with great skill. His tone was rich and dark, yet it was intense enough to be heard over the band even in the tutti sections.

As saxophone soloist and section leader with the United States Army Field Band, Sergeant First Class Tedd Griepentrog performs a great deal. The Army Field Band is the premiere touring concert band for the Army. It was formed in 1946 to be a band that would travel throughout America and the world as a musical representative of the United States. The band is called the Musical Ambassadors of the Army and it is exactly that, not only in this country, but around the world. I asked him what makes the band different from the other military bands in the Washington area.

“The Army Field Band is a unique organization in a lot of different respects. Most of the groups in the Washington area do ceremonial work, a series of public concerts, and one tour annually. However, our primary focus, under the direction of the Army’s Chief of Public Affairs at the Pentagon, is to travel throughout the country and the world representing the American military and instilling patriotism. We provide free concerts all over the world, and the response is just tremendous. It’s because our performances revive a sense of patriotism in our audiences. At the end of each concert, people are on their feet jumping, cheering, and crying, all at the same time.”

The band, which consist of sixty-five musicians plus a thirty-member chorus, was an official musical representative of the U.S. at the 50th anniversary of the D-Day ceremonies in June. That European tour included concerts in England, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. Tedd recalled his impressions of playing for several different presidents and heads of state in Normandy for the 40th anniversary of D-Day ten years ago. “The impact of being there with the people of France and with the original soldiers, sailors, and marines who were part of the invasion was unforgettable. I remember driving through parts of France that were not specifically involved in the World War II commemorations; the people would recognize us from the signs on the bus and give the ‘V’ for Victory, forty years after the event.”

Tedd attributes the universal success of the band to the quality and professionalism of each band member, to the leadership and support of the band from the podium and Pentagon, and to a programming philosophy that reaches every audience. “We perform for the musically uneducated public, so our programs are much lighter than what you would expect from a typical college wind ensemble. We will start with a march and then play a standard overture, one that people usually will recognize from the classics. Then we program a vocal solo, a Broadway medley or standard aria in transcription, and follow it with an original composition for band, like the Holst Suites. After that comes an instrumental solo, and we usually close the first half with a light movie theme collection. The second half begins with a twenty-minute set by the Soldiers’ Chorus, which might include a condensed musical done in costume or a medley of patriotic songs. After another march, we play a big band medley (Glen Miller) or bring the Dixieland band out front. We wrap it up with some patriotic songs, such as Stars and Stripes Forever, and everyone goes home happy. This is a proven format. We have five or six standing ovations during each concert. We have found that audiences want to hear music that makes them feel good, that has a tune that they can recognize, and that creates an emotional response in them.”

“I think my focus as a recital artist has changed as a result of that. I play some of the avant-garde pieces, but, in general, I tend to shy away from it in my programming. Let’s face it, two hundred years from now when people look back at what music has survived, only the major works and the best music of the outstanding composers will remain. We must include on our programs something from individual time periods that represents music as a whole, not only twentieth century works.”

Tedd Griepentrog is a product of the great, Midwestern, saxophone country. He grew up in Milwaukee. Some of his early influences were the many fine saxophonists that he could drive three or four hours to hear live, such musicians as Fred Hemke at Northwestern, Donald Sinta at Michigan, Eugen Rousseau at Indiana, Jim Forger at Michigan state, and Bob Black in Chicago. He always wanted to play the saxophone and started in the sixth grade. His high school had a very strong music program and a terrific band director named Terry Treuden, who was also a saxophonist. Karri Schulte-Brich, a music major at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, was his first saxophone instructor. She was a very caring teacher who had the rare foresight to know when she had taken him as far she could. While Tedd was still in high school, she moved him into the studio of Stan DeRusha. “It was an interesting Wednesday night for Stan. Joe Lulloff would come in for a session with him and I would come in and wrap up his evening. I hope he enjoyed those nights. After putting in whole days at the university, to have the two of us back to back had to be a challenge. We were throwing everything at him we could find. Stan really taught me how to play music. He was a tremendous influence on me in my early career. We played some etudes, but mainly Stan introduced me to the standard literature. As a high school student, I played the Ibert, the Bozza Improvisation and Caprice, and the Maurice Tableaux.

“I studied with Jack Snavely at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He was a former Joe Allard student, so he emphasized the physical and analytical aspects of playing. Many of my teaching techniques and practice regimen come from Jack. He was also a great doubler, who encouraged me to study all the woodwinds. That doubling emphasis paid a lot of bills in my early career. I strongly encourage playing multiple instruments.”

After college Tedd took a job at one of the five junior high schools in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where he taught three concert bands, three jazz bands, two jazz combos, and a Dixieland ensemble, plus lessons. Tedd calls it “one of the shining lights in public education.” As well as having a fine music program, the administration was enlightened about professional development. They let him have a personal day off whenever the Milwaukee Symphony called him to play. “It was a marvelous opportunity. Not too many saxophonists have the chance to perform with a professional orchestra; it is an experience that I feel is extremely beneficial. You are in a position of being a soloist within an ensemble. I got the job in an interesting way. While I was still in college, I did a lot of performance competitions I lost one that had Russell Dagon, the principal clarinetist with the symphony, as a judge. After the judging was over, Russ asked me if I would be interested in playing with the orchestra. Within a month we were on a road trip to New York and playing the Alexander Nevsky of Prokofiev at Carnegie Hall! So my first professional experience was at a very high level. I continued to perform with the Milwaukee Symphony as their first-call saxophonist for four years, until I moved out East.

“Russ Dagon was a tremendous influence on my playing. I ever heard him play a wrong note or ever have a problem with a reed. We were playing the Bizet L’Arlesienne Suite and he was playing the little half-note, quarter-note countermelody as if it was the most beautiful song in the world. That’s music. The simplest little melodies in the hands of an artist like Russ will grab people and yank their hearts out. My exposure to him was great for me.

“Actually, Russ was part of a situation that helped cure me of performance anxiety. One my first performances with the symphony was playing Pictures at an Exhibition. We had a guest conductor who, during the bassoon vamp, cued the saxophone solo two bars early. My life flashed before my eyes. I thought my life as a musician was over! I looked over at Russ and saw him shaking his head and mouthing the words, ‘No, don’t play!’ Although my heart was thumping out of my chest, I started the solo where I thought it should be and, at the end of the movement, the conductor flashed an ‘OK’ in front of his white tie as if to say, ‘Thanks for covering for me.’ Everyone has performance anxiety at some time or another. Nervousness, especially as a soloist, is normal. Getting over the anxiety that performing in front of people can create is a major accomplishment as a musician. Having lived through that predicament, and realizing that my career didn’t end because of someone else’s mistake, helped me to get over my performance anxiety.”

The jazz scene in Milwaukee also left a lasting impression on Tedd. He was exposed to many name jazz and classical artists who came to Chicago and automatically played Milwaukee, too. At this time in his life, Tedd was playing a lot of jazz, big band, and commercial jobs. I asked him if he felt that jazz has had more of a positive or negative effect on the saxophone

“Obviously, the more exposure the instrument gets, the more people will want to play the horn and the more people will excel on it. The standards of playing the saxophone have continued to climb over the last hundred years. We have students today who are playing pieces that were called unplayable ten years ago. I think we as saxophonists have grown. The whole profession has changed and improved.

“The problems arise when the general audience doesn’t recognize the difference between the sound of a concert saxophone (that is, the recital, soloists, orchestral, and band players) and a commercial saxophone (the studio, jazz, film score, and musical theatre pit players). You can’t use the specialized equipment of a commercial artist in a concert band. The concept of blend and balance within the ensemble disappears if you do. Younger students need to either pick middle-of-the-road equipment that will allow them to play both styles fairly well or ask someone who can help find set-ups that will work for each style. Even in the Field Band, as we move from a solo piece to a big band medley, the whole section picks up different equipment. It helps establish more of the style and sound of each work. In the Mood shouldn’t sound like Capriccio for Soprano Saxophone and Band.”

After a year and a half at Kenosha, Wisconsin, Tedd auditioned for his position at the Army Field Band and he has been happy with it for over ten years. “I am very fortunate that I am blessed with a terrific job, one that puts me in the face of the American public and saxophone players and musicians around the world on a regular basis. But I’m also blessed with a terrific family who is supportive of what I do. I simply couldn’t do what I do without their support. You understand that my family is spouseless and fatherless for almost half the year because I’m on the road. Over my twenty-year career, I will be gone for over six years. That’s six years of my children’s growth and development that I can’t get back. Regardless of what I have achieved in the saxophone profession and what will live on as a result of that, it is my family that I leave behind.”

While on the road, Tedd manages to keep most of the standard literature under his fingers by practicing in the hotel rooms. He has a great deal of expertise in the earea of saxophone solos and ensembles accompanied by band and is constantly looking for music in this combination that “features the lyrical and technical potential of the instrument.” He has compiled a four-hundred-fifty work catalog of literature that most people don’t even know is available for all the saxophones and saxophone ensembles with band or wind ensemble accompaniment. “Hopefully, my work in this area can serve as a resource for saxophonists working with bands. Actually, the service bands in Washington do more saxophone features annually that the sum total of the rest of the world’s saxophonists. We have had a lot of works written specifically for us that are now standard pieces in the repertoire.”

On the day of our interview, Tedd was in rehearsal playing a piece written for him in 1993 by Jim Richens, Capriccio for Soprano Saxophone and Wind Ensemble. I was favorably impressed with the Army Field Band in rehearsal and very excited to hear the shaping of a new solo piece for the saxophone. In our interview, Tedd expressed his concerns about the quality of literature for his instrument. “What bothers me about the bulk of twentieth century literature is that is seems that the composers wrote it because they know the saxophonists didn’t have a long history of great literature and that anything they wrote would get played. The quality is just not there. I like to sit down with a composer and ask if he or she understands the parameter, what works on the instrument and what doesn’t. I certainly believe that you should be able to go back to the composer after the piece is finished and suggest changes that will improve the work. Every way to make the piece work musically, to make it easier to play should be discussed with the composer.”

On a concert of Americana played at the Berlin Philharmonie one year before the Berlin Wall fell, Tedd soloed on A Tribute to Rudy Wiedoeft. The band performs this style of music because it appeals to all audiences. In fact, foreign audiences tend to connect popular music with America. “The Wiedoeft Tribute may not be the pinnacle of most saxophonists’ repertoire, but it is a viable part of the saxophone’s history and a part that the general public can appreciate and enjoy. While I have mixed feelings about playing a piece like that, the response is invariably the same: the people jump to their feet in an automatic, standing ovation. We have tended to program Americana for the audiences in those countries because we represent America in an official capacity. It is amazing to me that, wherever you play in the world, everyone knows Stars and Stripes Forever. Music really is the universal language.”

Much of the music Tedd plays is arranged by staff arrangers in the Army Field Band and is not available to other performers. “We are a military organization that is funded by the government and the music arranged for us involves copyright clearances that are exclusive for our use. However, some of the pieces written for the Washington, D.C., saxophonists have been published. Ken Dorn has provided a terrific service to us all in taking a financial risk by publishing so many manuscripts. And, in specific instances, non-service saxophonists have received permission to perform an otherwise unavailable piece arranged by our staff arrangers.”

Most performing saxophonists have heard this comment from the number of admirers following a solo performance, “I didn’t know the saxophone could sound like that!” Of course, it is meant as a compliment, but it also points out that the general public has preconceived notions of the saxophone sound being less than musical. Tedd is committed to changing those beliefs by performing a great deal, educating young players wherever he goes, and by adopting a very personal approach to tone. “My sound tends to be a dark sound, yet it needs to project over the large ensemble. As a result, I use a fairly stiff set-up, particularly on soprano. When people find out I’m playing on a Yanagisawa 7, they wonder why I use an open facing in a legit performance. In truth, it gives me the flexibility to play with the refined, controlled sound and the nuances I need in the quartet, but it also enables me to step out in front of the band and play with the projection I need, yet with the darkness I prefer.

“The instrument is only limited by the person playing it. This is one of the things I try to convey to players everywhere. There is no reason that we can’t take that big hunk of plumbing that looks like it came from under the sink and make the soft sounds that we associate with the flute or play it as loudly as a trumpet or as brazenly as a trombone. This instrument, more than any other I know, has the ability to do everything. The tonal realm is so diverse. Look at the different people who play it. They are all blowing on the same horn, yet there are so many different tone concepts. The technical capacity of the horn is also unlimited.”

Regarding the question of tone vs. technique, Tedd is adamant. “Whatever you play must first and foremost sound good. I don’t care if it’s a whole note or thousands of notes in a sonata. We are creating a sound by blowing into a horn and vibrating a reed. What happens with the fingers after that has nothing to do with the tone concept. It must start at the face with the reed, mouthpiece, and air.”

Chamber music is another of Tedd’s responsibilities with the band. The saxophone section has formed a quartet in the standard SATB arrangement. “I prefer the SATB format in quartet literature because it allows for a different voice. Even in different ranges, two altos produce one voice or timbre, whereas the soprano offers another sound. However, the soprano can be a problem for young quartets, since younger player might not be able to control the nuances and pitch problems of the soprano; the result is usually a trio with the soprano on top. For this reason, I suggest the AATB format for younger players.”

With all the performing Tedd does, I wondered about his warm-up and practicing routines. “I probably spend more time with the horn in my mouth than most other players, and that’s fine since my sole focus is as a performer. The band rehearses two to three hours a day and we often spend the afternoon working in chamber ensembles. We have a very active chamber music series that performs throughout the Baltimore/Washington area. The quartet plays regularly on it.

“My warm-up is shorter than most because it seems as if there is not enough time between playing to have to warm-up! It’s as if my reeds don’t get a chance to dry out at all. Generally, I warm-up with flexibility studies for my embouchure. Long tones are standard for developing dynamic range and consistent pitch. When I’m limited in time, I tend to concentrate on the extremes of the horn, which don’t come as easily. I do a lot of low register studies, pinky exercises, to make sure that the horn is going to respond, the reed works, and my fingers are warmed up enough to do what they have to. I go from there to the top of the horn, from high C on up, working particularly with the palm keys to make sure that the reed will respond Then on to the altissimo range.”

Tedd’s commitment to quality teaching is realized in the master classes, clinics, and coaching that he does while on tour. He heads a new program where soloists and chamber ensembles work with college students during the tour. “We try to hit a band rehearsal or recital hour where we can play for the students and then break off in to master classes. It’s a marvelous opportunity for us since we don’t have much chance to work with students; it is a great chance for students to see someone making it in the professional field. It’s a completely unique program that the Field Band offers and one that we enjoy a great deal.”

Over the past thirty years, it seems that the saxophone has become increasingly more popular as an instrument for beginners. Given this trend and the highly competitive world of professional musicians, I asked Tedd to speculate on the future of the saxophone in educational and professional circles. “I know of places in the country where there are saxophone discouragement programs. As an ex-band director, I certainly understand the concept, but I really hesitate to discourage anyone who wants to become involved in music. Regardless of whether the students grow up to be professional musicians, players in community bands, or just pull out the horns once every five years, the experiences and musical knowledge that they gain are carried with them the rest of their lives. However, the academic community needs to be honest with students about their future. We need to say to our students that the standards are rising and here is an assessment of your abilities and limitations. Let’s not encourage students to enroll as majors as a recruiting effort to keep your studio alive. That is a disservice to the profession!

“I believe that we are musicians first, and that we need to approach the saxophone as musicians. Looking at the literature we are playing and what we are teaching our students, I see that we don’t expect as much of them as the violin, piano, or vocal teachers do in the next studio. We desperately need that same standard. It will take time and people who are insistent enough and have great integrity. I would just say to future students, ‘Never settle for being just a good saxophone player; settle only for being a great musician and then try to improve beyond that.’”

For Tedd Griepentrog, this has become an overriding credo. Through the Army field Band, he is living this philosophy in his frequent performances, his continued and caring education of young players, and a personal dedication to raise the standards by which his instrument is measured. All of us, musicians and audiences alike, benefit from his efforts and are enriched by his successes.

Copyright © 1995 Saxophone Journal

Published in the January/February 1995 Edition

Reprinted with Permission. All Rights Reserved.